“When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say'st,

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

(From “Ode on a Grecian Urn” by John Keats, 1819.)

In these dark times, while wondering what to do with myself knowing so many are suffering horrifically, then realising that what I, like everyone else who is lucky enough to be safe, have no choice but to do is my job, the last lines of John Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn” have strangely started doing an ironic little jig in my head.

Mainly because of their potential double-meaning. Or at least, two of the possible readings one can apply to the poem’s conclusion.

The first option is of course to take Keats’ lines at face value.

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty, —that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

I think a lot of people in, say, the fashion industry or art world subscribe to this. Or at least, to the idea that their mission is the creation and propagation of aesthetic beauty and that is all. In other words: beauty is their truth, their raison d’être. Beauty brings pleasure, even reassurance doesn’t it? It’s a privilege to have the time and resources to create it, but it can, after all, be spread to bring comfort, or at least entertainment to the many… Can’t it?

I will admit, for example, that I personally felt a comfort I couldn’t put my finger on, alone in front of the Rothkos at FLV the other day.

Implied in Keats' last lines is also the suggestion that we shouldn’t attempt to find concrete answers to everything. And that since you can never be sure anyway, it’s ideal to create something beautiful without a specific message and leave a little mystery.

But for some reason all this also reminds me of the current fiery debate around whether people with a large platform for reasons entirely other than expertise in world politics or international diplomacy (ex: fashion/ art/ styling/ interpretive dance/ trombone playing) should weigh-in on subjects as weighty as Israel-Palestine.

Should the individuals whose job it is to seek, create or interpret aesthetic beauty just shut the F up and let others seek, and interpret, well, truth? Or is it everyone with a heart’s moral duty to use whatever platform they have to denounce injustice? “There there”, Keats seems to say with a pat on the head. “Truth is beauty after all. Now stay in your lane, fashionista.”

But wait. What!? And not call out wrongdoing to a captive audience? Sits ickily, doesn’t it? I agree.

Then again, people demanding that creatives on Instagram pronounce their opinions about the war, or even denouncing individuals for not coming out with strong statements on either side should ask themselves: are they themselves showing up to work each day in a T-shirt that reads “Free Palestine” or “Am Israel Chai”? Would they? Or refusing to show up to work at all for that matter. Because this is effectively what they’re asking people whose business depends in any way on social media to do.

Ok ok but but but! What if we divide the last line in two and let “truth is beauty” sit alone for a sec. Truth itself is the most beautiful thing on earth to many: there are those who believe that the seeking and transmission of facts is the most purposeful use of one’s time on earth.

My husband’s job for the past three weeks has been to make as comprehensive and responsible a documentary as possible about Hamas for a popular French TV Channel (up all night, on deadline, interviews with experts who have spent years on the conflict taking place in our living room while I try to keep the kids quiet, etc).

Maybe inversely, my job is to help people forget about Hamas for just a couple minutes a day, when they really need to, for their own mental wellbeing. This is to say, there’s a pretty solid reminder in my living room that the soup I’m making right now is different from the soup he’s making.

And before we go cursing the patriarchy—our roles may as well be reversed. I studied journalism, he did not. Things just played out this way. So far anyway… (cue Marc’s big fashion debut…)

Hang on though. Some critics have suggested that Keats’ last two lines are in fact, ironic. After all, they’re not spoken by Keats himself, but by the beautiful urn before him (note the quotation marks). In this interpretation of the poem, Keats is in fact dissatisfied with the “cold pastoral” of the urn, sitting there smugly, luxuriating quite pointlessly in its own aesthetic glory.

If we choose to follow this interpretation, the logical conclusion is that the poet is in fact pouring scorn on the urn for being so wilfully “silent” —in its purposeful attention-seeking but refusal to tell more about the history and culture that it has witnessed down the ages. Maybe Keats is in fact lamenting, bemoaning even the limits of art and the aesthetic world in that it offers only partial messages, or worse, no decipherable messages at all?

Or maybe Keats was saying he liked the fact that art maintains an aura of mystery around us, around itself, that not all facts are immediately made readily available through it, that it makes us ask questions rather than telling us the answers.

Apparently the former interpretation is more likely to be the accurate one in terms of Keats’ intention. We gather from his later letters that he was a fan of something he called ‘Negative Capability’: “that is when a man is capable of being in his uncertainties, mysteries, doubt, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason”. (Keats goes on to praise Shakespeare’s talent for this). This negative capability is evident in the mysterious nature of the urn, which offers the viewer partial glimpses and hints of a long-vanished civilisation.

But I think I’ll bullishly go ahead and prepose a third, modern interpretation. One which is admittedly not inconvenient to yours truly.

If the “truth" that you yourself are best suited to propagating is artistic, maybe this is in fact your greatest role when, for humanity, the going gets as rough as it is right now. Facts obviously shouldn’t be meddled with, and those that spend their careers seeking and reporting them are of the utmost importance in our society. But if your vessel for touching others is indeed “beauty”, maybe you should put it forward for others’ sake (/for art’s sake?), simply in view to create comfort for your audience (and, consequentially, yourself?)

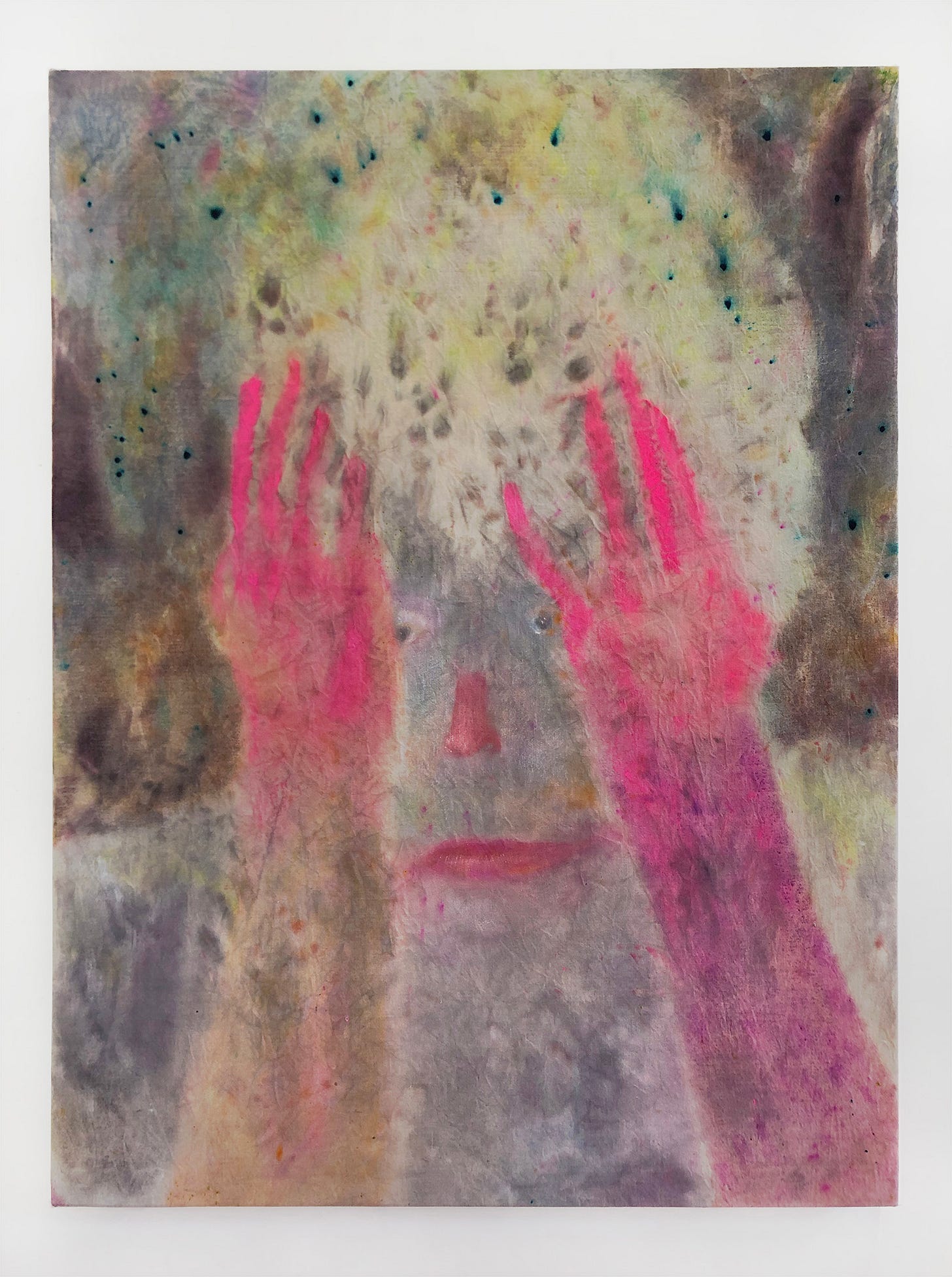

Here, for example, I am thinking of the Sofiane Pamart’s breathtakingly passionate piano recital I was lucky enough to witness a couple weeks ago. The Olympia concert hall was at capacity but you could hear a pin drop during his pauses. We all needed the intense beauty of his notes, and you could feel it. Or Loren Erdich’s ‘Me, Myself, Pretending Not To See’ (below) which I couldn’t look away from for ages after coming across it the other day. She posted it, but did not say what she meant by it in the caption.

If, meanwhile, you are someone whose work people follow for aesthetic beauty and then you take it upon yourself to explain world conflicts on your platform, you obviously believe you are doing your audience a solid: exposing them to the truth. But isn’t it your version of the truth after all? And, in as polarising a situation as the one unfolding currently, isn’t sharing such personal interpretations of the truth —interpretations you bring to the situation based on your own lived experience —ultimately serving only to solidify tensions and further polarise the greater public?

In other words, is the tireless social-media in-fighting actually helping anyone actually affected by the conflict? Helping the children suffering on either side? I embrace the importance of being an active citizen —I am never more moved by the power of each individual’s civic duty than at a march, or when voting, both experiences actually make me sob uncontrollably — but does your local representative even know what you posted about on Instagram? Shouldn’t you start by calling or emailing them if you want change, rather than perpetuating the race to the bottom in terms of shock value and righteousness that Meta’s algorithm promotes?

“Just because something goes viral, doesn’t mean it’s true,” wrote the singer Pink on her Instagram the other day. I admit I wasn’t expecting to hear from her on the topic but she made me think. Actually, she made me think as much as her song “Just Like A Pill” made me think about the nature of toxic relationships as a teenager (a lot).

The social media generation (of which I am admittedly a part) has made it so that everyone is potentially ripe for their 15 minutes of fame and we are all capable of becoming opinion-leaders. We are all, also, potential members of one-another’s audiences. And as audience members, isn’t it important for us to consider who we are going to for what? In other words, if your opinion leaders gained their followings and notoriety by being style leaders, music leaders, comedy leaders, poetry leaders, are they in any way legitimate in terms of forming your opinion on Gaza?

I should say, with full transparency, I hope to be considered an opinion-leader on areas I have researched and reflected upon for years: French culture, certain women’s issues I focus on, heck, miniskirts! But I bloody well know when I am out of my depth on Israel-Palestine, and while I have read endlessly about the history of this conflict and am drowning myself in podcasts and articles covering every side, I know even if I continued this way for the next five years I would probably still not be legitimate. Everyone has the right to their opinion and my intention with these words is not to silence anyone, but rather to suggest that as Socrates tells us, intelligence can also be “knowing that I know nothing”.

Also, as Guardian columnist Jonathan Friedman put it recently: “This is where you wind up when you view this conflict in monochrome, as a clash of right v wrong. Because the late Israeli novelist and peace activist Amos Oz was never wiser than when he described the Israel-Palestine conflict as something infinitely more tragic. A clash of right v. right. Two peoples with deep wounds, howling with grief, fated to share the same small piece of land. So, this is not a football game […] for one grimly obvious reason. There are no winners - only never-ending loss.”

Where social media is concerned, I would propose one way in which we individuals with followings but without expertise on the subject can make ourselves useful, which is sharing humanitarian organizations that actually do help those who are suffering in this conflict, and encouraging people who normally come to us for ideas on where to invest their money to invest it there.

Take heart. Maybe hundreds of years from now, people will look back at your creative output, whatever it is, and glean some important truth about the autumn of 2023 after all. The kind of truth Keats is ostensibly trying to glean from the Urn. Maybe this is the best we creative-types can hope for in terms of leaving our mark. Maybe it will help stir more common humanity after all, even on social media, than taking sides. Maybe simple, connective humanity is not so meaningless after all.

Maybe, maybe not.

I don’t have the answers but I do have…

Weekly Recs (!)

Read: Am deep into Ann Patchett’s new novel Tom Lake. Simple, connective humanity overflows from this warm bath of a book. Plus it’s narrated by none other than MERYL STREEP on Audible.

Need: Mazarin Paris’ new Pave Eboris Link ring represents connection and harmony with its dual links, and a new high for its young Parisian designers with its delicate, unique design. A lovely gift idea.

Listen: Can’t get enough of The Rest Is Politics podcast. Two pals with a world of experience from opposite ends of the political aisle discuss international affairs and British politics with just a palatable hint of cheeky banter. Very informative for such an easy listen.

Beautifully written and so thoughtful - love the way you keep revisiting and reinterpreting the poem

This is a beautiful and articulate post. Unfortunately it is rare to see A post that describes the nuance and complexity to this heartbreaking conflict .